June 30, 2016

Tohoku and the World: 5 Years Since The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami

Keywords: Civil Society / Local Issues Disaster Reconstruction Newsletter

JFS Newsletter No.166 (June 2016)

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

Starting in August 2015, JFS has been organizing meetup events to discuss sustainability-related issues in English. There has been quite a variety in the programs, including presentations by guest speakers visiting Tokyo at the time, a climate-talks role-playing simulation exercise, and a discussion about food issues over a lunch with a variety of Japanese traditional millet grains as alternatives to meat.

Tokyo Sustainability Meetup

http://www.meetup.com/Tokyo-Sustainability-Meetup/

The sixth meetup, held on April 6, 2016, featured the theme of five years since the Great East Japan Earthquake, and JFS invited two guest speakers who have been dedicating themselves to disaster relief and reconstruction support. They delivered presentations about the realities in the affected areas at the time of the disaster, and changes that have occurred over the past five years, as well as current conditions and emerging challenges. JFS also gave a presentation about a visit to Fukushima.

Report from Fukushima: Five Years after the Great East Japan Earthquake

http://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id035527.html

This edition of the JFS newsletter introduces a presentation by Robin Lewis, International Coordinator at a Japanese non-profit group called Peace Boat.

My name is Robin. I am half Japanese and half British. My mother's family is partially from Tohoku, originally from Sendai two or three generations back, and my father is from Wales. I grew up here in Japan, the U.K., and also in Hong Kong. I graduated from university in 2011, where I studied business, but just as I was about to graduate, the tsunami and earthquake happened, in March 2011. When it happened, my family was over here in Japan, so I came back, very soon after the earthquake and tsunami. After the disaster, I spent a few months in Tohoku helping out with a number of nonprofits and relief groups, and then spent one year working for a corporation in Tokyo.

Now, I work in disaster risk reduction and response, both in Japan and abroad. I'm the International Coordinator for Peace Boat, a Japan-based international NGO, and I'm based here in Tokyo. I am responsible for my NGO's programs related to natural disasters abroad, which covers a range of different countries. Having worked in Tohoku since 2011 in different capacities, I'm somewhat familiar with Tohoku, but I am not an expert! In the past few years, I've been focusing on international projects, such as responding to the earthquake in Nepal, Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu, and Hurricane Sandy in the USA.

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

Here is a quick introduction to the organization. Peace Boat organizes voyages on a passenger ship that travels around the world, visiting different countries and implementing educational and exchange programs in these countries. By visiting different places, interacting with people from all walks of life, and learning about social and environmental issues in these areas, it is possible to foster people-to-people relations and build a more peaceful, sustainable world. The ship travels around the world usually three to four times a year, and also embarks on one or two regional voyages, visiting more than 60 ports worldwide during the course of the year. We work closely with local partners in the countries we visit to implement these different programs.

Peace Boat has many focus areas -- everything from human rights, to conflict prevention, to nuclear weapons abolition -- and we have lots of different projects happening throughout the year. One of the big focuses is disaster relief. The first disaster relief project took place in 1995, after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, or Kobe Earthquake. Since then, we've been working in over 15 countries worldwide. In Japan, we do lots of domestic emergency relief work, from this big earthquake in Kumamoto in 2016 to flooding and typhoons, which happen year after year in Japan.

(click to view large image)

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

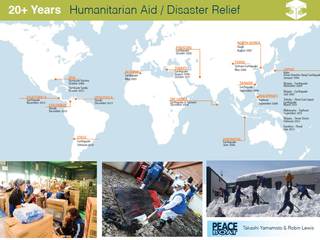

If you look at the map, you can see that we have been active in many different places, including Chile, Guatemala, Nepal, the United States, and the Philippines. While we do work internationally, we maintain a strong focus here in Japan on disaster projects, both in Tohoku and other disaster-affected areas.

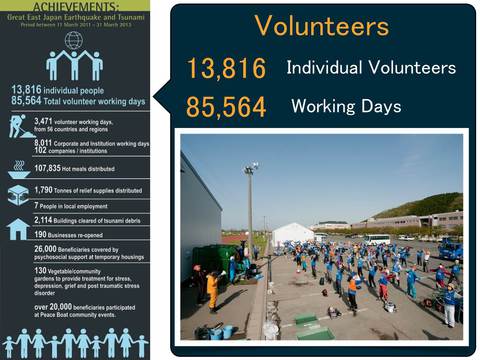

What happened after the Tohoku earthquake in 2011 was that Peace Boat established a separate organization to work specifically on disaster relief. We set up an office in Ishinomaki, and have our headquarters here in Tokyo. I will now introduce some numbers related to our projects. Peace Boat coordinated one of the biggest mobilizations of volunteers by one organization in Japanese history. We mobilized over 13,000 individuals for 85,000 work days, which is quite a staggering figure. Based in Ishinomaki, we continue our work to this day there and in the nearby town of Onagawa.

(click to view large image)

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

We were privileged to have over 3,470 work days contributed by non- Japanese volunteers, who represented 56 countries. They joined us in Ishinomaki and took part in a range of relief projects, such as distributing hot meals, and relief supplies -- things like blankets and household goods -- to the survivors.

One of the major focus areas for our work was clearing debris from homes. Mud, wood, and other debris had entered homes during the tsunami and needed to be removed, so we coordinated energetic volunteers to remove it from the houses. In many cases, it was very difficult, especially for elderly people, to remove this kind of debris. We were able to provide teams of volunteers to work with residents to do that.

That's a brief overview of what we have been doing since 2011. Now we are focusing on long-term recovery, such as supporting Ishinomaki's fisheries, and providing assistance to displaced people living in temporary housing. We still have a full-time office in Ishinomaki to manage these long-term recovery projects.

I'd like to give some figures that can help to paint a picture of what is happening now in Tohoku. The peak number of evacuees, in May 2011, was approximately 470,000 people. For reference, if you think of the population of Iceland being 323,000, this is the bigger than the entire population of Iceland. Currently, 171,000 people are still displaced, called "hinansha" in Japanese. This information I looked up today (Apr. 6, 2016) is the most up-to-date information I could find. These figures make the situation more real. A very large number of people is still displaced after the nuclear disaster, including in Fukushima Prefecture.

Next, I'd like to share some information about the number of people living in temporary homes -- pre-fabricated homes set up by the government after the tsunami. Currently, approximately 90,000 people are living in temporary homes in the most-affected areas of Miyagi, Iwate, and Fukushima prefectures.

Originally these temporary homes were only supposed to last two or three years. But as we all know, 2016 marks the fifth year since the disaster. Some people say that the condition of the homes is sub-optimal due to the length of time that people have been staying in them. But some residents may remain in temporary housing until as late as 2018.

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

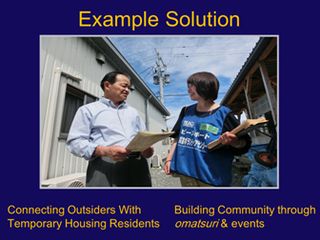

Now, please let me introduce some of Peace Boat's work in Ishinomaki, five years after March 2011. The first is the Kizuna Newsletter project, where volunteers print and distribute a newsletter to hand out to people who are living in temporary homes. While they are handing out newsletters, they're having conversations with the local residents. A significant portion of people living in temporary homes are elderly people. After the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, there was a phenomenon known as "kodokushi" (meaning "lonely death"), where people were dying alone, because there was no social safety net. So the idea here is that if we can coordinate volunteers to go to each home to see how they are doing, it's a subtle way of doing "mimamori," or "watching over the community" and building people-to-people relations. Residents say that this kind of community interaction is very useful.

I'll give you a few examples of things that are happening in Ishinomaki. I talked about a couple of case studies. We are working a lot in the area of temporary housing. About 19,000 people currently live in these temporary homes. It is easy to generalize, and say that people living in temporary homes are miserable, and yes, there are undoubtedly many challenges for people living there. But I don't want to over-simplify a complex situation. There are also, of course, many positive people living in these places leading very productive and prosperous lives. Overall, there are a number of challenges here in the temporary homes. They are generally built on flat land, facing schools and playgrounds -- basically anywhere that could be built on. Immediately after the earthquake, many people went to shelters and evacuation centers, for days, weeks or even months.

Roughly eight months after the earthquake, in October 2011, the last emergency shelters (in Ishinomaki) closed, and people were transferred to temporary housing or to alternative housing, such as relatives' homes. If they had enough financial resources, they could rent or buy a new place. Temporary homes were one of the government-provided housing options for people displaced by the disaster. The rent is free, but the residents have to pay for utilities such as electricity, gas, and water.

We have noticed a number of things when talking to the people who live in this area. A number of psychosocial issues are still prevalent, when we look at issues like alcoholism, domestic violence, and post-traumatic stress syndrome, or PTSD. Again, a significant portion of the population here is made up of elderly people. There's also reportedly something of a poverty gap. Especially now five years after the disaster, people are moving to new places, renting homes or going to public housing, but in some cases, people cannot afford to move. For example, people living on pensions or who have low incomes.

There's also a big challenge for community-building. Especially in the beginning, lots of people moved to new temporary housing sites where they did not know their new neighbors. As you can imagine, it is very hard to build a close-knit community in such a situation. But now, in many temporary housing areas, there is a strong sense of community because people have bonded with their neighbours.

The number of temporary housing residents is decreasing. In Ishinomaki, people are moving out, so there are some housing complexes with reportedly as little as 30 percent occupancy rates. I have heard that some that have several empty houses, which can be a bit intimidating for remaining residents. If the surrounding temporary houses are empty, people may feel isolated. A lot of people are going to post-disaster public housing -- this is again subsidized by the government. It's not free. It is subsidized, so people still have to pay rent, based on their income. From what I have heard, access to these new apartments is decided by lottery. People have to submit application forms, and they are able to choose preferred locations. Many of these housing blocks are still under construction in and around Ishinomaki. In some areas, I have heard that building may continue until 2018, which would mean that at least some people may have to remain in temporary housing until 2018.

Also, there are reports of increasing costs of materials, things like concrete and steel being used to rebuild infrastructure and homes in the affected areas. I have heard that this rise in prices may be at least partially caused by demand driven by the upcoming 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, amongst other factors.

A key challenge is the change in some of the communities in temporary housing where some people have been living for almost five years and have developed a strong sense of community. People are increasingly moving to alternative, more permanent, forms of housing, such as post-disaster public housing. However, when they move to a new place, there's another challenge. How do you build a strong sense of community when you are surrounded by strangers? This is the challenge that has been faced in some temporary housing communities in Tohoku since 2011, and which may affect post-disaster public housing going forward, as large numbers of people move.

There might be a positive impact by coordinating people from the outside to go to Tohoku to build relationships with residents, and also to build communities through festival events.

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

Another area of Peace Boat's activities is supporting fisheries. The output or productivity of fisheries in Ishinomaki has reportedly returned to 80% or 90% of pre-disaster levels. But the average age of fishermen is quite high, and that's one key challenge. Many young people may be more interested in going to bigger cities like Sendai, to pursue corporate or other careers.

The fishers say that market conditions are sometimes volatile. Prices fluctuate. Some say that the market is stabilizing a bit, but harmful rumours related to the release of radiation after the Fukushima nuclear disaster may have had a big effect on the market price of marine products.

Some young people are not interested in being fishermen, as it is perceived by some to be a tough job. So how is it possible to sustain this industry? One example of a solution is Peace Boat's Imacoco project. This is a homestay system in which people from outside the region stay with fishing families and work alongside them in the fisheries. In return for their labor, they are given accommodation, fresh food, and the experience of a lifetime.

They take part in work such as oyster cultivation and seaweed harvesting. Over the course of this project, several people relocated permanently to Ishinomaki to pursue fishing as a career. Additionally, approximately 30 participants moved to Ishinomaki to work part-time in Ishinomaki's fisheries after taking part in the project.

Copyright Peace Boat All Rights Reserved.

We also have introduced an "oyster ownership" system, called "Kaki-no-Wa." The idea is that people can buy oysters through this system, knowing exactly who the fisherman is, visit the oyster farm, and even join the fishermen on their boats to cultivate the oysters. It is an interesting way of connecting consumers and fishermen. It really opens up new markets for oysters and promotes a deeper level of engagement between consumers and producers.

As another example of impacts resulting from this project, there is the story of a student in Tokyo who enjoyed eating "kaisen okara gyoza" (dumplings made from seaweed, seafood and okara which is by-product from soy milk production) during his stay in Tohoku. He saw an opportunity because there was a strong need for halal foods (prepared according to Islamic law) at his university. He began to import the kaisen okara gyoza from Ishinomaki and sell it in his university. Now he is exploring the idea of selling the product in Indonesia. From this project, a number of exciting new projects and business opportunities like this have been born.

Japan is one of the countries most at-risk from earthquakes, typhoons, volcanoes, and other natural hazards. We must ensure to take the lessons learned from previous disasters and implement them in different communities to enhance the levels of disaster preparedness. This sharing of knowledge and best practices is in one crucial way to connect Tohoku's experiences with the rest of the world.

To wrap up, here are some points to consider regarding the current situation in Tohoku. People are forgetting about the disaster with every year that passes, which is not a surprise. However, it is important to ensure that people have some kind of connection to Tohoku, and through these connections, enable them to do something to support the recovery. Many NGOs are running out of funding or scaling back operations, partly because people are forgetting about the disaster.

Of course, whilst there is still a need to provide certain kinds of support, it is important to remember that all assistance to Tohoku should promote independence and build the capacity of communities to get back on their feet without external support.

I would like to add my observation that disasters exacerbate pre-existing problems. For example, places like Ishinomaki were experiencing depopulation and seeing an increasing rate of aging. The disaster did not "cause" these issues, but it did accelerate them, and made them worse. These types of demographic issues are very complex, as you can't just force people to move back to rural areas. There needs to be sustainable solutions to these challenges.

On a final note, here are some suggested action steps that you could take if you are interested. The first is to volunteer with organizations like O.G.A. for Aid, Peace Boat, and many other groups working in Tohoku. You could also show your support through tourism. There are many different tourism-related initiatives happening in Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwate. One example is TOMOTRA, which is actually organized by a group of high school students who conduct bus tours around Fukushima. It is great to see young people who were affected by the earthquake now creating new business opportunities to help with Tohoku's recovery.

Also -- I just heard about this one yesterday -- the Minamisanriku city office is organizing a tour for experiencing disasters. Participants take a bus tour of the area, and experience a simulated earthquake. They sleep in an empty school with minimal resources, using candles and limited water to survive. This kind of experience might be interesting to some people!

Also, many e-commerce services allow you to buy things from Tohoku through co-ops, individual farmers and fishermen in these areas. The websites of the Yahoo Fukko Department (Reconstruction Department) and Iwaki-no-Jyuni-Nin (known as "The 12 Leaders" ) offer many products from Tohoku as well.

There are also many events in Tokyo to support Tohoku, like the one JFS has organized today, and different farmers' markets, such as the Aoyama Farmers' Market, which sometimes sells produce from Fukushima, Miyagi and other places. Also, the Ueno Matsuzakaya department store has display of local products from the Tohoku region and is doing a special campaign to sell products from that region at the moment.

And finally -- and this is an area where JFS is really creating an impact -- spreading the word and raising awareness of these issues both in Japan and abroad.

That's it from me! Thank you very much for listening.

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses