April 30, 2015

Shimokawa Town, Hokkaido: Establishing an Energy-Sustainable Small Town Management Model with Local Forest Resources (Part 2)

Keywords: Energy Policy Newsletter

JFS Newsletter No.152 (April 2015)

JFS held a symposium on February 9, 2015, "Community Initiatives for Survival--from a Local Economy / Regional Revitalization Perspective," to which front-running practitioners in local community development were invited as guest speakers.

In our last issue, we introduced the first part of a lecture by Takashi Kasuga, then-Executive Director of Future City Project Headquarters at Shimokawa Town, Hokkaido (Mr. Kazuga was subsequently elected to the position of Shimokawa Town Councillor). Last month's article focused on the demographics, resources and economics of Shimokawa Town's initiative to establish a sustainable town using forest resources. This month's article will focus on the "human" side of this revitalization program.

Shimokawa Town, Hokkaido: Establishing an Energy-Sustainable Small Town Management Model with Local Forest Resources (Part 1)

http://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id035217.html

We are also undertaking "carbon accounting," which measures not money but carbon. Townspeople use bikes instead of vehicles as a way to decrease carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. They can also fix CO2 by using wood. In terms of carbon volumes, if people strive to plant forests and create a wood-based society, the carbon balance improves. If they emit less CO2, the overall carbon balance improves. I am wondering if we can get funding for creating a favorable carbon balance in collaboration with urban areas where CO2 emissions are unavoidable.

Let me introduce an example. When townspeople bring wood residue such as branches pruned off of trees in their gardens or forest plantations into wood material manufacturing facilities, they get a gift certificate worth \500 (about US$ 4.17) per 100 kilograms. This initiative enables us to secure fuel, even though not in significant amounts, and reduce CO2 as well as garbage volumes.

While only 145 people obtained certificates through this project in 2010, more recently this number increased to 760, which means that about one fifth of Shimokawa's population is participating. Some people say they participate because they want to decrease CO2 emissions and some say because they can get 500 yen. My plan is to ask the townspeople to participate in the project for the purpose of minimizing CO2 emissions, with a view to obtaining carbon trade funds from cities to put to work to further our aims.

The "Natural Capital Declaration" was launched at Rio +20. Soon after that, Shimokawa Town signed the "Shimokawa Natural Capital Declaration" in 2013. Today, when supply chain management is becoming more popular, mainly companies and financial institutions are trying to figure out how they are placing a burden on the environment, not only in terms of CO2 emissions, but throughout the entire process from production to consumption of goods. Our town has already evaluated the value of natural capital in Shimokawa.

In the first part of my talk, I noted that "Shimokawa's intra-regional production value amounts to 21.5 billion yen (about US$179 million)," but we found that its natural capital amounts to about 100 billion yen (about US$ 833 million) according to calculations based on data and basic methods used by the science council of Japan. The forests owned by Shimokawa are valuable. To enjoy their benefits, we are thinking about inviting companies and individuals to invest in our forests. As we set up various types of projects relating to forest maintenance, we are also planning to build a mechanism for investment in forests.

In an aging Japanese society, the ratio of people 65 years old and over to the total population in Shimokawa is 38 percent. The town provides detailed services designed to deal with aging society issues. One is a community bus, which stops anywhere within a certain zone by request. People can also make an appointment to have the bus pick them up and bring them back home.

Share-ride taxi service is also available for the elderly to visit a hospital if a reservation is made not later than the day before. A benevolent monitoring service for the elderly is provided using the optical cable that has been installed throughout the town. Another monitoring service uses a sensor installed in people's refrigerators that blows a whistle when the fridge is not used for a day.

Another service is shopping support: Support personnel stock a small pickup truck with daily commodities bought from local shops and tour each district of the town. The elderly can make their purchases without the insecurity of ordering items sight unseen.

In one part of Shimokawa Town is a settlement with a population of about 140, of which 53 percent are elderly. In this settlement, the town built a plant to produce heat, not from fossil fuel but from wood waste, in order to supply heat to welfare facilities. Battery chargers for electric vehicles were also installed at this plant. In the process of re-building public housing, the town built a collective housing facility that accommodates 26 households, where the elderly and the young live together using heat from the heat plant. With smart meters installed in each household, the safety of residents can be monitored.

Though electricity provided to the collective housing facility is not from renewable resources, residents can use electricity at extremely low prices thanks to a bulk contract. Electric power costs have been reduced through peak cutting made possible by arrangements regarding the use of electricity, hot water and energy among the elderly and the young; this also helps community building.

Because Shimokawa Town has heat produced from biomass resources, Oji Holdings Corp., a paper manufacturing company that was starting up a medicinal plant business, established a research institute for plants with medicinal properties in Shimokawa Town. It is well known that licking the inner bark of yellow birch is good for the stomach, and wild plants are blessings of nature which can be used to heal the sick. What pulled the trigger for this company was that the town has heat and energy resources. As I said earlier, "Where there are energy resources, industries will emerge." New businesses are bound to emerge where energy resources exist.

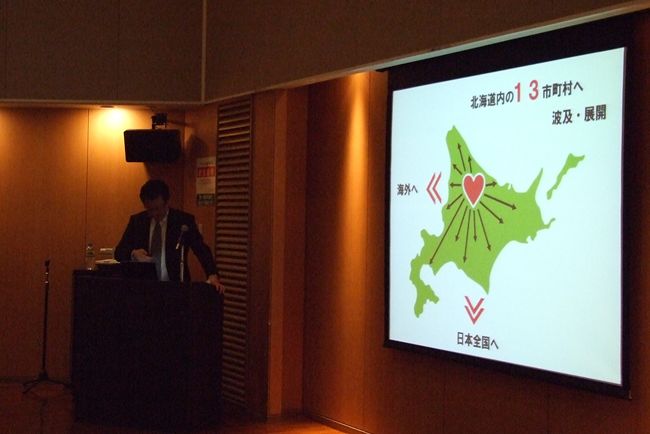

Mountain villages in Japan have been steadily losing population since 1960. The population of Shimokawa has also been decreasing after its peak in 1960. Thanks to the various efforts I have mentioned, the number of people moving in exceeded the number moving out over the last two years for the first time since 1960. The number of workers in agriculture and forestry is increasing in Shimokawa Town, while it is decreasing in neighboring towns and villages. Population loss seems to have been halted by our efforts. More human resources and money coming in and fewer going out have no doubt had beneficial effects on the regional economy, population and production as they circulate within the region. Decreasing population can be overcome. I believe that this can also be a model for regional revitalization.

Shimokawa Town is promoting these initiatives in an effort to create a sustainable regional society. The Japanese word for economy "keizai" is obviously based on the more comprehensive concept of "keisei-saimin" which incorporates the idea of not only making money but also of governing local communities and helping people make a living. In short, its ultimate goal is to achieve sustainable livelihoods and improve the well-being of people in the region. In 2009, the French president at the time, Nicholas Sarkozy, also said that the actual state of economy and the society cannot be represented by GDP alone.

The consensus in Shimokawa is that unless the town sustainably maintains its farm land, mountains, agriculture and other key industries in its area (about the size of all of Tokyo's 23 wards) the town cannot consider itself sustainable. In large cities such as Tokyo, sustainability might be achieved by promoting the service and manufacturing industries. In the case of Shimokawa, however, land, agriculture and forestry are vital. To make these resources sustainable, we must plant trees continuously and promote sustainable agriculture. Otherwise, we cannot make our area sustainable.

Finally, let me tell you a basic idea for promoting initiatives. When you work on something, it is quite effective to focus your energy on a specific target.

According to a survey on the attitudes of small business owners, about 40 percent of respondents were indifferent to external matters, 30 percent had a vague interest, 20 percent were concerned, and 10 percent were concerned and taking some kind of action. In many initiatives including community building, it is necessary to help indifferent people achieve higher awareness, and encourage people to change their behavior as well.

Shimokawa Town is promoting its initiatives with this in mind. For example, we hold events as a way to raise awareness among otherwise uninterested people, and organize workshops and lectures by specialists to inspire people to act. We should act thoughtfully in the context of this kind of system.

When a town's policies are indecisive, they will often end up carrying out halfway measures which fail to satisfy both indifferent and concerned people. We need to develop separate policies specifically for people who are indifferent and people who are concerned and/or engaged in activities. Otherwise, we will have difficulties and waste. This is the way we are promoting our initiatives.

Richard Florida argues, in his book "The Rise of the Creative Class: and How it's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life," that three factors, "technology," "talent" and "tolerance," are essential for revitalization efforts. Among these factors, we are paying particular attention to "tolerance" in the sense of an environment of openness in which people can feel free to say, "I will take the entire blame, so let's just do it!" We cannot move forward when we make a fuss over details. We will in any event have to take the first step. That's where tolerance is required. I believe that we can achieve revitalization by taking action based on this concept, although a certain amount of failure will be inevitable.

Written by Takashi Kasuga, Executive Director, Future City Project

Headquarters, Shimokawa Town, Hokkaido

Edited by Junko Edahiro

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses