January 30, 2015

The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: Achievements and Prospects from the Perspective of Citizens' Initiatives in Japan

Keywords: Education Newsletter

JFS Newsletter No.149 (January 2015)

Copyright Japan Council on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development All Rigts Reserved.

The year 2015 has now begun. The decade starting from 2005 was designated by the United Nations as the "UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD)." What have you heard about efforts for promoting new types of education under the aegis of the DESD around the world during the past 10 years? Towards the end of 2014, a World Conference was held in Japan to mark the end of the DESD. Japan Council on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD-J) was one organization that played a part in promoting ESD in Japan, and we interviewed its Secretariat-General, Ms. Chisato Murakami, about its achievements and challenges during the last 10 years since 2005, and about the Council's future goals as well.

---------------------------------------

The DESD was jointly proposed by the Japanese government and NGOs based on an NGO proposal to the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2002. After a UN resolution on the proposal was passed, the project was launched in 2005. ESD-J was established in 2003, at the request of the NGOs involved in making the original proposal. ESD-J is a networking organization, consisting of about 100 organizations and 260 individuals, with the participation of a variety of players, including NGOs, educational institutions, companies, local governments, teachers, and scientists.

This report outlines the achievements and challenges during the last decade, from the perspective of a civil society organization that promotes the ESD movement in Japan.

Citizens' Initiatives Join the Mainstream through DESD

Before the ESD concept surfaced, some alternative education activities aimed at solving various social problems were carried out by NGOs together with some teachers and citizens. Examples have included environmental education, development education, education for international understanding, and human rights education. These activities adopted the kinds of values and learning methods that are also important in ESD, such as participatory experience-based learning, student-centered learning, and empowerment of the socially vulnerable, resulting in the accumulation of the necessary know-how for carrying out ESD. Considering the crisis in the global environment, DESD provided a good opportunity to introduce such alternative learning styles into Japan's educational mainstream. This could happen because the Japanese education system is very centralized, and an educational revolution can spread quickly once the government decides to change.

One early, advanced example took place at Omose Elementary School in Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture in the Tohoku Region, where, in 2002, the school developed an original curriculum for all students from the first to the sixth grade. Its purpose was to teach how the students' daily lives and local industries relate to the core values inherent in the local environment, and how to visualize a sustainable future. This curriculum called for learning activities involving hands-on experiences in the field, and the cooperation of various people outside the school, including local museum staff, fishermen, and shopkeepers. To implement this program, they established an ESD council consisting of multi-stakeholders. In addition, they decided to extend their activities throughout the city with the support of the municipal Board of Education.

Another example comes from the Kyoyama District of Okayama City, Okayama Prefecture. This district has been committed to promoting various activities through local community learning centers, for example, action to protect and create clean environments (e.g. constructing paths lined with greenery and clean water) carried out on the basis of environmental inspections. These activities were approached in such a way as to involve the entire community from children to adults, with the participation of various actors such as schools, universities, local communities, enterprises, and NPOs. They incorporated awareness of multi-cultural coexistence and the production of films to record and hand down local culture and wisdom. Okayama City has actively promoted ESD by designating local community learning centers throughout the city, providing ESD coordinator training programs for city workers, and establishing an ESD ordinance.

These initiatives were accelerated by a project to designate of "Regional Centres of Expertise" (RCE) promoted by the United Nations University (UNU), and were showcased as a successful model involving local multi-stakeholders. (Currently, there are 130 RCEs throughout the world.) ESD-J published a textbook, "Learning from Each Other for Hope," which records in detail the process of how the ESD developed in local areas in Japan.

ESD at Schools Expands from the Top Down

Although ESD in Japan was initially launched by citizens' bottom-up efforts, it became much more visible in schools after Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) made UNESCO Associated Schools the basis for ESD promotion in Japan, took steps to increase the number of Associated Schools, and implemented support measures around 2008. The Japanese government's numerical target for increasing the number of UNESCO Associated Schools to 500 by 2014 was met in 2013, and the number of these schools exceeds 800 today.

To be certified as a UNESCO Associated School, the school must submit plans to engage in ESD-related activities on a regular basis. The participation of schools in this framework has resulted in a major achievement in that ESD activities formerly implemented by only a limited number of teachers were expanded to become a school-wide effort. In the past, one major issue had been that only diligent teachers worked hard on ESD, and these activities fell off when the teacher was transferred to another school.

In teacher training courses, participation and experience-based learning, learner-centered learning, and learning in collaboration with the local community are becoming more and more important and widespread. As ESD that involves collaboration between schools and local communities expanded, adults and children began to learn from each other locally, and an increasing number of communities have steadily become more interested in the program and experienced better community building. The themes being tackled have become increasingly diverse; food and agriculture, energy, disaster prevention, welfare, multi-cultural symbiosis, and cultural inheritance.

Holding the "UNESCO World Conference on ESD"

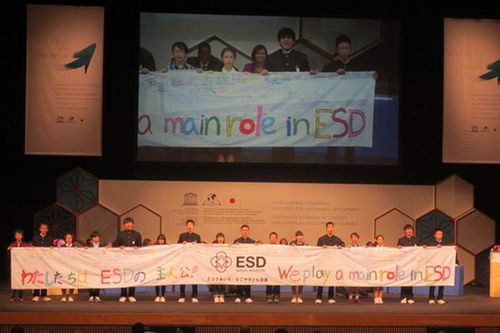

In November 2014, the final year of the "UN Decade of ESD," various events were held in association with the "UNESCO World Conference on ESD" in Okayama City (Okayama Prefecture) and Nagoya City (Aichi Prefecture). Over 1,000 participants including ministerial level officials from in and out of Japan reflected on the activities undertaken in the past decade and discussed measures for after 2014.

ESD-J started preparing for the World Conference from January 2014 by holding local meetings and policy proposal forums at 10 locations across Japan and compiled 13 proposals for formulating the policies necessary for ESD promotion after the end of the "UN Decade of ESD." Some points included in these proposals are: promotion of ESD through collaboration between schools and communities in each local community; nurturing and creating a platform for coordinators; including clearly stated ESD elements in school curriculum guidelines; and establishing a council consisting of multi-stakeholders and an ESD National Center to support local ESD.

ESD-J also called on about 30 companies that have expressed an interest in ESD to hold "ESD Corporate Leadership Forums;" these forums took place between April and October in 2014 and resulted in the "ESD Declaration from the Japanese Business Community," which provides a set of action guidelines for integrating ESD into business practices. Fourteen companies and economic organizations agreed to participate in this initiative.

In November at the World Conference in Nagoya, ESD-J gave a presentation to participants and representatives of UNESCO about citizen initiatives to promote ESD in Japan, and introduced "ESD Recommendations from communities and the civil society" and "ESD Declaration from the Japanese Business Community."

The importance of ESD was mentioned in the "The Future We Want," an outcome document of Rio+20 in 2012, which clearly stated that the global community should continue to tackle ESD after 2015. In spite of this, the recognition level of ESD is actually not very high in most countries. Hoping to achieve a breakthrough in this situation, the participants of the World Conference exchanged opinions on outcomes and achievements in ESD, issues relating to ESD promotion, and action needed to enhance ESD.

On the last day, a "Global Action Program (GAP)" was launched as a framework for ESD promotion after 2015, and an "Aichi-Nagoya Declaration on Education for Sustainable Development" was adopted. This declaration calls for a review of ESD values, invites governments of UNESCO Member States to expressly adopt ESD as a policy goal for education and development, and to strengthen ESD measures in their post-2015 agendas. We hope the international community will respond to this request and create ESD movements around the world.

Strengthening Cooperation for Promoting ESD after 2015

In Japan, a follow-up meeting was held on November 13, 2014, the day after the conference ended, sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and co-sponsored by the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This meeting functioned as an important venue for discussions on ESD promotion in Japan after 2015. About 300 participants attended and talked about promoting ESD at schools and in communities, involving youth, nurturing coordinators, and building networks for promoting ESD involving a diversity of sectors including government.

ESD-J has always considered it necessary for various bodies concerned with sustainable development issues to cooperate and collaborate together, and since the launch of the DESD, it has been working to convince the Japanese government to create a scheme where public and private sectors can work together. Action so far included a relevant ministries' conference in 2005 and the convening of a "Roundtable Meeting on the United Nations DESD" that included scientists, NGOs, educators and businesses in 2007.

United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014) Japan Report

http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokuren/pdf/report_h261009_e.pdf

However, it is difficult to say that this scheme functioned well - ESD promotion plans were in fact implemented independently by each ministry. Thus, the DESD ended without even a unified window of contact. The efficacy of discussing policies with stakeholders was expressed in each of five priority action areas incorporated in the Global Action Program adopted in 2014. In the present second stage of ESD starting in 2015, more energy needs to be expended on the implementation of policies formed by the collaboration of private and public sectors.

Copyright Japan Council on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development All Rigts Reserved.

Written by Chisato Murakami

Board Member / Secretariat-General

Japan Council on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD-J)

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses