January 24, 2012

Outcomes and Lessons Learned from Measures in Japan to Save Electricity in Summer 2011

Keywords: Newsletter

JFS Newsletter No.112 (December 2011)

Japan's experience in the summer of 2011 essentially functioned as a national experiment to see how society could live with a considerably reduced supply of electricity, and JFS has been reporting on the nation's efforts from many different angles in our newsletters. After the summer passed, the Japanese government summarized the results of the "experiment" and released its findings in a report.

The Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, and subsequent accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima resulted in a severe decline in the available supply of electricity. Meanwhile, some saw how the Japanese responded as showing the world a way forward, as it might be necessary to start reducing worldwide power consumption to address global warming. With the hope that there are things to learn from Japan's experience, we introduce here an outline of the government's report, titled "Follow-up Results of Electricity Supply-Demand Measures for this Summer," released by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in October 2011.

Follow-up on the Results of Electricity Supply-Demand Measures in Summer 2011

First of all, right after the disaster on March 11, Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) and Tohoku Electric Power Co. (Tohoku EPCO) implemented planned rolling blackouts for 10 weekdays during the period from March 14 through March 28 as an unavoidable and urgent measure. As the rolling blackouts caused significant disruption of industrial activities and people's daily lives, the two power companies did not implement any after April 8.

During summertime, when power demand increases sharply due to the higher use of air conditioning, large electricity users (enterprises with supply contracts for 500 kilowatts [kW] or more), small electricity users (businesses with power contracts below 500 kW), and households had targets set to reduce their electricity consumption by 15% compared to the same month of the previous year, until September 30, 2011.

In order to systematically suppress power consumption peaks, restrictions on electricity use at peak times were imposed, by law, on large electricity users in the service areas of Tohoku EPCO and TEPCO until September 9 and September 22, 2011, respectively.

In the midwestern part of Japan, all six utilities of the Chubu, Kansai, Hokuriku, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu electric power companies faced tight electricity supply, because many nuclear power plants under periodic inspection could not restart operations. Though the reserve rate -- an index to show surplus supply capacity -- should be at least 3% and normally more than 8%, the reserve rate of the six utilities this summer fell to 0%, and especially, that of Kansai Electric Power Co. (KEPCO) was as low as minus 6.2%.

In the service areas of the six utilities, legal restriction on electricity use was not applied, since the calls for electricity saving and flexibility were thought to be sufficient countermeasures during summertime. However, KEPCO requested people to reduce their electricity use by at least 10%, and the other five power companies asked people to try saving electricity as long as their daily lives and economic activities were not hampered, both for the period to September 22.

Major Measures to Secure an Electricity Supply-Demand Balance

Large electricity users were required to voluntarily formulate and implement plans for reducing their power consumption during peak times, for example by shifting their operation or business hours. At the same time, Article 27 of the Electricity Business Act, "Restriction on Use of Electricity," was enacted on July 1, 2011, to secure the effectiveness of demand suppression and fairness among electricity users.

For small electricity users, METI presented examples of electricity-saving measures related to lighting, air conditioning, and office equipment use, etc., and encouraged them to formulate and implement voluntary energy-saving action plans to achieve the target. Actually, about 100,000 offices in the service areas of TEPCO, Tohoku EPCO, and KEPCO formulated action plans. In addition, experts designated as electricity-saving supporters by the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy visited 150,000 offices and held explanatory meetings about 10,000 times in the TEPCO and Tohoku EPCO areas to support electricity-saving efforts.

METI's Launch of the "electricity saving support project for small customers" and the "electricity saving hotline" (telephone consultation office)

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2011/0610_02.html

METI's Addresses Summertime Power Problem with Supplementary Budget

http://www.japanfs.org/en/pages/031101.html

METI provided ideas for measures to save electricity to households and mass media outlets through newspapers, television, and various other means. It also distributed educational materials on electricity-saving measures to about 4,300 elementary and junior high schools in areas served by TEPCO and Tohoku EPCO, and promoted a participatory program for households called the "declaration of household electricity saving," which had about 150,000 participants.

In addition to approaches tailored for different kinds of users, other integrated approaches were also carried out. One example is a public campaign to encourage saving electricity that used various mass media such as newspapers, television broadcasts, and the Internet. Another was intensive information disclosure through measures to help visualize electricity demand and supply status, such as TEPCO's "electricity forecast" service. In the event of possible tight supply or rolling blackouts, the government prepared emergency alert messages to call for prompt electricity-saving practices, and planned to release electricity shortage alerts via TV and radio broadcasts, mobile phones, and community wireless systems. Fortunately, this was not necessary in the summer of 2011.

Outcomes from the Electricity-Demand Side

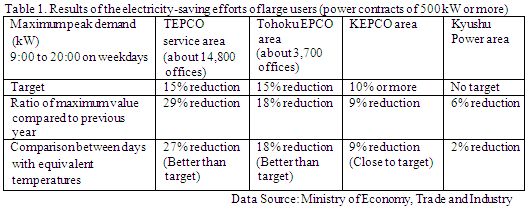

The following table shows the results of the efforts of large users (power contracts of 500 kW or more).

Direct interviews with about 30 companies revealed that electricity-use restrictions significantly affected some production and business activities, and caused considerable costs estimated to be from several hundred million to one billion yen -- about U.S.$1 million. The additional cost included increased labor costs due to shifting working hours to holidays and nighttime, usage of private power generation facilities, and production adjustments. On the other hand, some companies in service sectors succeeded in meeting electricity consumption reduction targets while minimizing the negative impacts of electricity-saving measures.

Here are the implications of what was learned toward forming policies for the coming winter, in response to the results shown above:

(1) When measures are mandatory, more electricity may be saved than the set targets (Tokyo, Tohoku). (2) Even when only a voluntary target is set, some electricity saving can be expected due to having a target, such as reduction of peak power consumption (Kansai). (3) To minimize the negative impacts on economic activities, it is necessary to request businesses, particularly in the service sector, to undertake detailed efforts to conserve electricity.

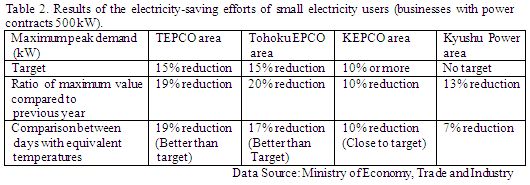

The following table shows the results of the efforts of small electricity users (businesses with power contracts below 500 kW).

The results of a questionnaire sent to about 230 enterprises revealed that there were impacts on production and industrial activities, including cost increases and a decrease of holidays due to the workers' shift changes at client firms. At the same time, some enterprises in the service sector (representing a large ratio), such as convenience stores, realized their 15% electricity-saving target with minimal negative impact. Specific examples of such initiatives are changes in use of lights (turning off some and introducing LED lights), air conditioning (set at 28 degrees Celsius), and having fewer elevators in operation, etc.

Here are the implications of what was learned toward policy formation for the winter: (1) Even when only a voluntary target is set, some electricity saving can be expected due to having a target. (2) To minimize the negative impacts on economic activities, it is necessary to request businesses, particularly in the service sector, to undertake detailed efforts to save electricity, while considering the differing circumstances of each company.

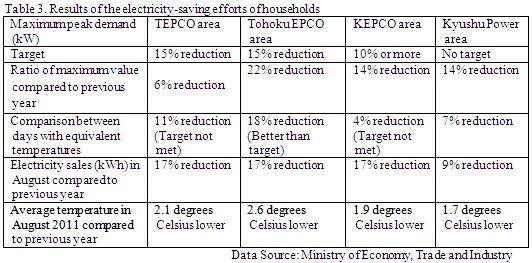

Finally, this table shows the results of the efforts of households:

As shown in the table above, many households failed to meet the targets for reduced electricity consumption during peak hours. In terms of overall electricity sales (kWh), however, the Tokyo, Tohoku, and Kansai areas all met the targets to reduce electricity use.

The results compiled from questionnaires sent to 1,200 randomly selected households in the Tokyo and Tohoku areas show that most people were able to save electricity within a certain level by expending reasonable efforts, while only a few people said, "It was not possible to save electricity (0.8%)," or "It was slightly unreasonable to save electricity (5%)." Some of the main techniques people employed included switching off lights during daytime and reducing the use of lights at night, setting air-conditioners at higher temperatures, and unplugging home appliances when not in use. About 90% of the households said that they would continue their electricity-saving efforts, and about 65% said that they would cooperate in reducing electricity consumption by 10% or more if requested.

Here are the implications of what was learned toward policy formation for the winter: (1) Even when only voluntary targets are set, it is expected that electricity will be saved through reasonable efforts by presenting households with electricity-saving measures. (2) Electricity use generally meets targets, while usage during peak hours is likely to remain below the target, thus requiring further exploration.

What can we learn from the national experiment conducted in the summer of 2011? One of the reasons previously used to promote nuclear power generation in Japan was that we would face electricity shortages without nuclear power, yet even though the number of nuclear power plants operated during the summer of 2011 was only 15 out of 54 across the country (as of August 6, 2011), the nation managed to avoid blackouts.

Considering the deep impacts on industry, however, continuing the same level of electricity-saving efforts will not be sustainable. The implications gained from these experiences will help us find better solutions for a society that consumes less energy with fewer negative impacts.

For the winter of 2011, the two service areas of Kansai and Kyushu where electricity demand is especially tight due to their high dependence on nuclear power have their reduction targets set at 10% and 5%, respectively, based on electricity use in the same month of the previous year. We will follow up on the results of the initiatives taken this winter and will update you when they become available.

Reference: Follow-up Results of Electricity Supply-Demand Measures for this Summer

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2011/pdf/1014_05a.pdf

Written by Junko Edahiro

Related

"JFS Newsletter"

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.4): 'Eightfold Satisfaction' Management for Everyone's Happiness

- "Nai-Mono-Wa-Nai": Ama Town's Concept of Sufficiency and Message to the World

- 'Yumekaze' Wind Turbine Project Connects Metro Consumers and Regional Producers: Seikatsu Club Consumers' Co-operative

- Shaping Japan's Energy toward 2050 Participating in the Round Table for Studying Energy Situations

- 'Good Companies in Japan' (Article No.3): Seeking Ways to Develop Societal Contribution along with Core Businesses